As stacks of nature writing books titter high in bookshops, and submissions for our prize proliferate into unheard-of numbers, it is clear that we have found ourselves in a glorious golden age of nature writing. Entering the tenth year of the James Cropper Wainwright Prize, which has flourished in popularity and support over the last decade in ways we couldn’t have imagined, we turn our eyes to the glow of nature books past – the stand-out books, the titans of the genre, the newcomers, and those changing and diversifying the genre for the better.

And why at this very moment in time have we found ourselves at such a pinnacle of nature writing? What propels us to connect with the natural world around us, to reckon with our place within it in new ways? Nature writing is a tide that tugs at us to rediscover our natural roots, pulling us back towards the open ocean.

‘Nature writing is a tide that tugs at us to rediscover our natural roots, pulling us back towards the open ocean.’

Most of us find ourselves entrapped in the commotion of modern life, consumed by technology, city living and often, individualism. It can be undeniably overwhelming, as if our anchor to the present is lost somewhere just out of reach, our holistic sense of the world faded. In this drought of modernity, we have found ourselves reaching towards an oasis of nature writing: books that can subdue, reconnect and revitalise us. Accomplished writing can reignite in us a fire to appreciate and protect our surroundings.

It was during the Covid pandemic that many of us discovered or rediscovered our affinity with nature. While the world stopped, nature continued, its rhythms and cadences pulsing on. In the morning birdsong, the flight of a bird, the sinking sun, or the soft changing of the leaves, time could be felt, even when all else ceased. Our Prize slogan at that time was, ‘Let the outside in’, as not all of us were lucky enough to be able to get outside. Nature books served to ground us when the solidity of the natural world remained just out of grasp, seen through a foggy pane of window or from an apartment balcony, but not felt under our feet. Both reading and nature books blossomed at this moment, as our time to read, reflect and notice increased. It seems these invaluable ways of thinking have been carried onwards, into our present moment.

‘In the morning birdsong, the flight of a bird, the sinking sun, or the soft changing of the leaves, time could be felt, even when all else ceased.’

Our prize’s history begins with the remarkable figure of our namesake Alfred Wainwright: fell walker, mapper, writer and illustrator. His legacy runs deep amongst nature enthusiasts, most keenly felt in his popular guidebooks, the Pictorial Guides to the Lakeland Fells, which are meticulous and intricate in their detail. Wainwright revolutionised the way we interact with the natural world, combining fact with artistry. In his own unique way, he was not only able to map out the fells on which he walked, but he also captured their distinctive character. This year, the prize comes full circle as we return to Alfred Wainwright’s roots and hometown, Kendal, burrowed in the sublime peaks of the Lake District, for a festival-style celebration of this year’s winners, who undoubtedly continue his legacy in their writing.

Our last ten years of platforming the best nature writing has been a rich journey, navigating stories of our natural world. The Green Road Into Trees was the inaugural winner of the Wainwright Prize, in which travel writer and film-maker Hugh Thomson charts his odyssey across England, through ancient trackways and green grass roads, from coast to coast, exploring the past and present of his homeland – the legends, literature and natural worlds that have shaped us, including the subterranean cultures of Celts, Saxons and Vikings that lie closer to home than we may imagine. Likewise, the celebrated Robert Macfarlane’s canon of work is a lyrical exploration of the landscape’s interconnectedness with language and storytelling. His Wainwright-Prize-winning book, Underlands, is an exploration of deep time, myth, memory and human experience. Like Orpheus, he travels into the deep pits of the underworld. He writes, ‘I have rarely felt as far from the human realm as when only 10 metres below it, held in the shining jaws of a limestone bedding plane first formed on the floor of a warm Cretaceous sea’. Humanity feels small in his work, a speck in the history of geological time.

‘Humanity feels small in his work, a speck in the history of geological time.’

John Lewis-Stempel, British author, farmer and naturalist, is our only double-winner of the Prize. His first winning title, Meadowland, is an ode to the English meadow, seen through the rural year; it is an opera of the hidden lives of its inhabitants who scurry and burrow amongst the grass blades and beneath the trodden earth. His later work, Where Poppies Blow, shifts in focus, movingly telling a story of affinity between World War One soldiers and nature in the trenches. Lewis-Stempel writes, ‘In the trenches, soldiers actually habited the bowels of the earth, in direct and myriad contact with all flora and fauna of Flanders and the Somme. Nature was all around, in every one of Its/His/Her guises’. Where soldiers fell and shells soared, the shoots of spring emerged. Nature was a source of solace for those men who fought: birdwatching transpired, nature poetry abounded, and trench gardens were cultivated.

Our third winner of the prize, Amy Liptrot’s The Outrun, radiated like the Merry Dancers she searches for in Orkey’s Northern night sky. Hers is a vulnerable and candid account of addiction and healing. Lost in a hedonistic, alcohol-driven cycle in London, Amy finds herself washed-up in her once-home of the remote Orkney isles, fractured, lost, and wounded, amid memories of her childhood and her past: ‘When I first came back to Orkney I felt like the strandings of jellyfish, laid out on the rocks for all to see. I was washed up: no longer buoyant, battered and storm-tossed’. Immersing herself in the icy currents of the North Sea, beachcombing, observing puffins nesting on sea stacks and seafowl circling, she is pulled towards recovery. A rich and spatially textured work, Liptrot maps the spaces in between city and wilderness, musing on what is lost in the tides and then eventually returned to us.

Nature writing is, of course, primarily about nature, but its depth and complexity is bottomless, as it constantly evaluates and re-evaluates our relationship to the natural world, interrogating concepts such as place, time, and belonging. Nature is not only natural, but social, historical, political and philosophical. And while there are books that place the self in nature, exploring our connection and interconnectedness to nature, there are also works that are more educational and polemic in their stance; a call to action for us to save our dwindling natural resources and protect our vulnerable planet, to face the raging forest fires, devastating plastic pollution and brutal wildlife destruction that engulfs our earth. This latter genre propelled us to create a new category of nature writing in 2020 – the Prize for Conservation.

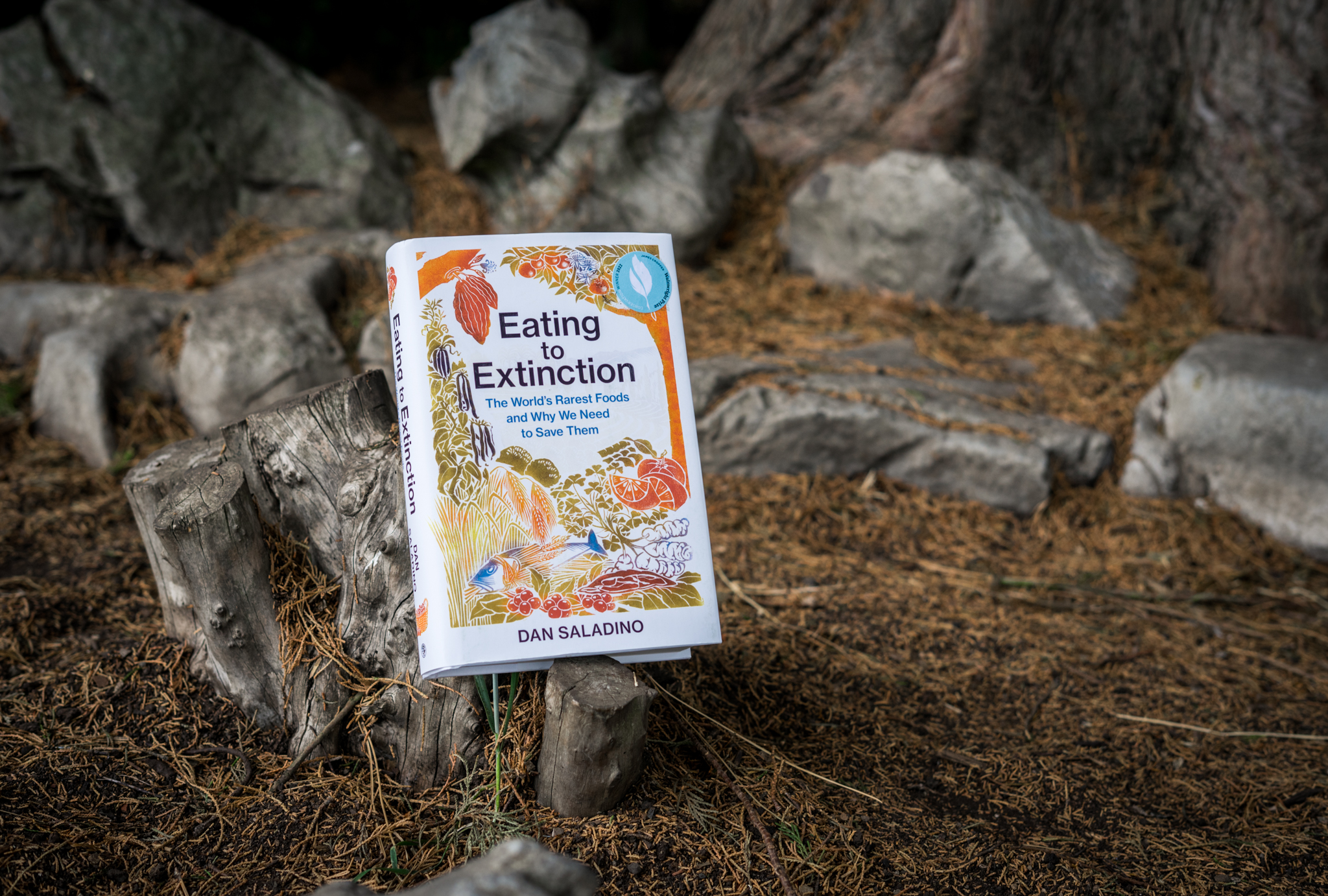

While attitudes to the right way to conserve and protect our planet may vary, the same fervent desire lies at the heart of this genre of books. Benedict Macdonald’s Rebirding claimed the first Conservation title, followed by Merlin Sheldrake’s Entangled Life, and last year, Dan Saladino’s Eating to Extinction won the Prize. These works are rich in variation: a compelling manifesto for restoring Britain’s wildlife and restoring rural jobs; the secret and incredible lives of funghi; the foods that are at risk of being lost forever and the stories behind them. To quote Merlin Sheldrake, ‘Words form stories and stories shape our senses and imaginations. Our senses and imaginations allow us to enter into relationships with those around us, whether human or non-human’.

![]()

![]()

![]()

And with this drive for conservation has emerged the global climate youth movement, a passionate and inflamed collective of youth activists determined to do something concrete about climate change and to save their futures. From this cast of heroes is our very own Wainwright Prize winner, Dara McAnulty, the youngest person yet to win a major literary prize. McAnulty claimed the 2020 Nature Prize with his deeply-felt memoir, The Diary of a Young Naturalist. Charting a year in his life from Spring equinox to the following Spring equinox, Dara moves from one side of Northern Ireland to the other, finding respite in nature, and uncovering how his love of the natural world is intertwined with his autism.

Speaking to us, Dara proclaimed modestly and compellingly that, “This book feels like a youth voice. For me, that feels like the most important thing, that maybe, just maybe, some other young people might see this book, and might think about taking up their own voice”. He continues, “I just want to hear everybody else, all these young people out there and their voices, and this prize means that bit more to me because it feels like youth voices can be heard, and we can, even in the world of literature – which has always been seen as older, especially nature writing – be heard. I’ve proved to myself that younger people can write about these diverse and incredible issues, while also exploring the natural world that we live in”. This year, we welcome another brilliant young activist, Mya-Rose Craig, into our hold with her longlisted work, Birdgirl, a story of the joy and consolation she has found in birdwatching.

“This book feels like a youth voice”

In recognition of the central role of children and young people whose words, speeches and rallies have changed the narrative around nature, we introduced another vital and timely category last year – the Children’s Prize for Writing on Nature and Conservation. Brothers Rob and Tom Sears were awarded the inaugural prize for their richly illustrated book and imaginative story, The Biggest Footprint, and Dara McAnulty found himself once again on a Wainwright Prize shortlist the following year for his children’s book, Wild Child: A Journey Through Nature, which felt only fitting.

As McAnulty rightly pointed out to us, ‘Every single voice that we add to a discussion diversifies and enriches it’, and it is refreshing to witness the changes in publishing that have happened in the nature writing industry over the last decade. And for the first time in our prize’s history, this year’s shortlist has been dominated by female writers. The notion of the aloof, male, Romantic nature writer is losing its footing, and something more diverse is emerging. The stories and connections that different people have to the land and sea are coming to the surface, buried as they have been by the types of narratives that have taken centre stage. The right to claim land and one’s place in it is a complex issue, and the ability to naturally feel at home or to ‘belong’ is often a privilege. This year’s longlistee Mya-Rose Craig is also a campaigner for equal access to nature via her organisation Black2Nature, and we are so grateful for figures such as her who are changing this space in order to allow diverse stories to flourish and be told.

Whether authors are celebrating their relationship to nature, writing a political manifesto to tackle climate change, or illustrating a children’s book on the wonders of the natural world, each story is theirs to tell, and each narrative is further drawing our attention to the wildlife on our doorsteps.

Explore this year’s incredible shortlist here.

Privacy Policy | Terms & Conditions | Website by Milk & Tweed

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |